Summer project begins the Game Development School’s initiative to create augmented reality/virtual reality (AR/VR) games for those with physical disabilities.

Video games are made to be fun and challenging, but few are made to be therapeutic. Now there’s Adventure Bay, an augmented reality game designed for children with cerebral palsy, that students from the School of Game Development spent their summer creating.

Led by Game Design Lead Steven Goodale, the team conceived of Adventure Bay as a tablet-based hub of mini-games that focus on various movement disorders and conditions associated with cerebral palsy. These symptoms often appear in early childhood, and can involve issues with sensation, vision, hearing, swallowing, and speaking.

“I teach students that a lot of the time you’re not making a game for you, you’re making a game for somebody else,” Goodale says. “[I tell them] do your best to understand what your end-user is like and what they can do.”

By the end of summer, Adventure Bay included two games: “Fairy Duster” and “Balloon Shark.” Each was designed with very simple goals, guided by physical therapists from Avalon Academy, a Burlingame, Calif., private school for children with movement disorders, and California Children’s Services Medical Therapy Unit in San Francisco’s Sunset district.

The advisors suggested the games be simplified to exercise gross motor movements, such as pronation and supination (the ability to rotate wrist palm up or palm down), and pilot a wheelchair.

“We spent a lot of time thinking of what would be appropriate and what kind of actions these kids can take,” said Game Development student Alex Agcaoili, who worked on Adventure Bay as a designer and program lead.

In game design, “playtests” are instrumental in pointing out where a game soars and where it needs more work. But creating games for children with cerebral palsy is especially challenging because every user is different.

According to Avalon Academy’s Director of Movement Education Brenda Huey, there were occasions when games on the popular Wii platform were used to work on arm motor control and balance. But generally, she says, children and young adults with moderate to severe physical disabilities are not always represented in mainstream activities and entertainment.

“It is really wonderful that this group wanted to use the latest technology to create an AR game specific for the kids I see,” Huey says. “Adventure Bay is a platform for endless possibilities to integrate purposeful movement and function into a well-packaged game that kids want to play.”

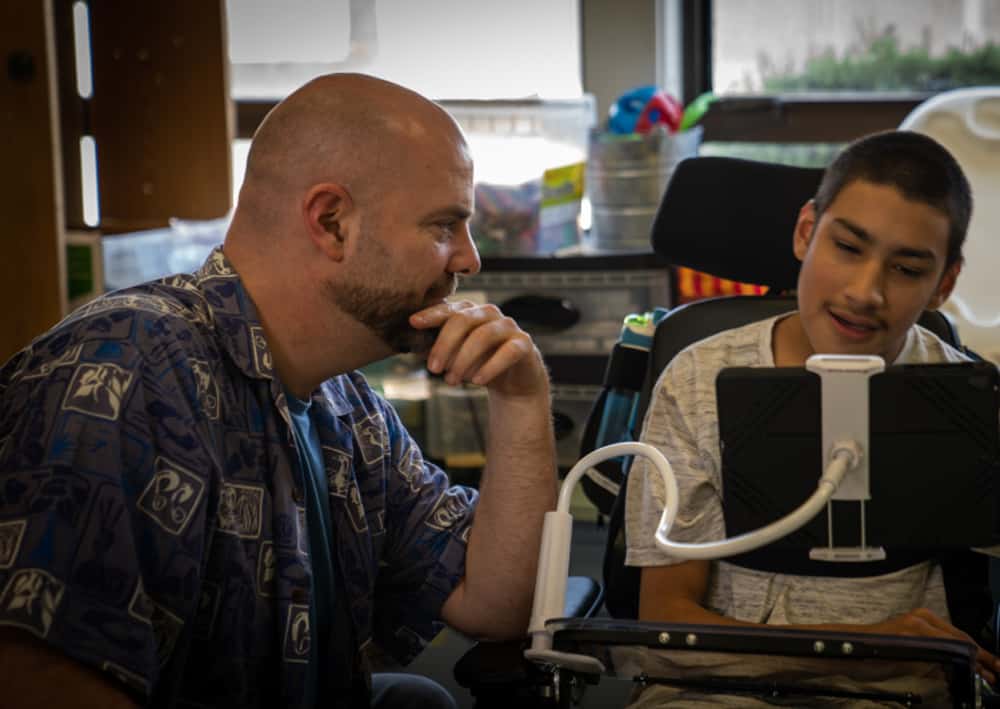

On a demo day held in August, 2018, Adventure Bay “visited” both institutions. Tested by five students ranging from 9 to 16 years old, Goodale said this initial cluster of patients provided a lot of good feedback on what to improve…while also allowing users to have fun trying out the games.

Speaking of one user named Anjelo, who is learning to drive his chair by pressing controls with his head, Goodale recalls that the game’s augmented reality “was compelling enough for him to drive right to the spot.”

Goodale notes the varying nature of the users’ symptoms—one was able to walk but had issues with her vision; another deferred his eyes from too much visual noise. From the playtests, Goodale said the Academy team gained insight on how to make the game more accessible. “[The game] wasn’t immediately intuitive,” he says, “and you want games to be intuitive if they can be.”

As ambitious as the Adventure Bay therapy game project was, Agcaoili believes getting a demo into therapists’ hands and to others working in the field is a huge accomplishment by itself. “If we get more people who can use the technology, who understand cerebral palsy, who really know the direction to go in, this project could explode,” he says.

Goodale and the Adventure Bay team are setting plans to move the project forward. He says addressing issues within the software prototype, building out the center hub and possibly adding another mini-game are first priorities. But he’s hoping to obtain backing from more sources, internal and external, in hopes that developing therapy games becomes a regular part of the School of Game Development.

“I’d like that to be an ongoing concern for our school, where we’re going to devote a regular part of our development power, every semester, toward working on pro-social games and building out therapy games in AR/VR. I think it’s the kind of thing that we need to pay more attention to. We need to think about it as a target for what we do… creating a game that has a positive impact on someone’s life.”

*****

Learn more about Adventure Bay

Article by Nina Tabios, Publications staff reporter for Academy Art U News

Photos by Christina Marapao