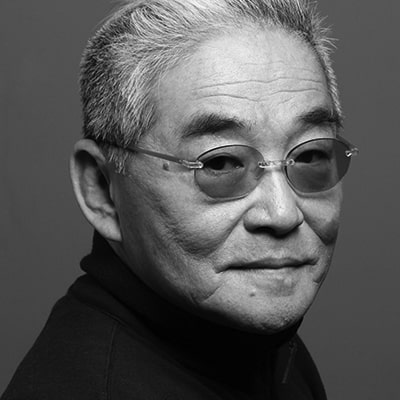

He jokes that he’s a “one hit wonder,” but Tom Matano beamed like a proud papa when his major hit—the Mazda Miata—celebrated its 25th anniversary in early September at an event that lured nearly 3000 fans and their respective two-seaters.

Matano showed up at Mazda Raceway at Laguna Seca in Monterey, Calif., on September 5 for more than just a party and weekend of activities and talks (including his own keynote speech on the origin of the Miata).

What he really wanted to see was the mystery that had been occupying his thoughts for weeks: the new fourth-generation MX-5 Miata.

Matano has been executive director of the Academy of Art University’s School of Industrial Design since 2002, bringing his distinctive blend of energy, discipline and design savvy to the task of ensuring his students are ready from day one to contribute innovative designs to 21st-century employers. He’s a big part of why the Academy’s Industrial Design School was recently ranked fourth of all such schools in Europe and North America by Red Dot, a prestigious global organization dedicated to advancing product design.

A Father for 25

Notwithstanding his academic accomplishments, Matano is still known as “the father of the Miata” in automotive circles. His office on the Academy campus is filled with stacks of miniature car models, mementos from his travels and photos of Miata gatherings around the world. On the wall, there’s also a copy of the final student project that ultimately launched his career: a futuristic-looking rendering of a 1974 Pontiac.

Within months of creating the Pontiac design, Matano was hired by General Motors. He moved to Detroit equipped with great design potential and naiveté, and he reported every day to work, even weekends, eager to learn as much as possible.

He didn’t realize he’d be compensated for every hour, and upon receiving his first paycheck, told his supervisor it was “too generous.” When, a couple of years later, the U.S. was in the midst of an energy crisis and layoffs in the automotive industry, General Motors transferred him to its Opel operations in Australia.

After a few years as an assistant manager at Opel, Matano moved to Germany to work for BMW. He admired the brand and was eager to study its aerodynamics—but hated the cold weather in Munich. Before long, he accepted a position at the Southern California design studio of Japanese company Mazda.

At Mazda he worked on the third-generation RX-7, a sporty coupe. But the project that really took hold of him was the design of a new, lightweight sports care to be introduced at a realistic price point.

Matano, who was raised in Japan, envisioned the car with a distinctly Southern California sensibility. It would be, he wrote in his notes in 1986 (three years before the model was completed), “a quality car that has great fun-to-drive personality and has a cheerful character.”

Also in 1986, Matano, already a visionary, wrote a 25-year roadmap for the car’s future—including three anticipated generations that would take the car beyond the new millennium. He foresaw that the car would have a cult-like following, inspiring car clubs around the world, and no matter the year, would still be recognized as a Miata 100 yards away.

The Miata took five and a half years to complete, a longer “gestation” time than most cars, Matano says. “We knew it was a special car for us,” he recalls. But he never imagined the car’s lasting impact.

When the Miata was eventually introduced at the 1989 Chicago Auto Show, Matano says, the acclaim was second only to the 1964 Mustang. The car was so popular, Mazda suspended the employee discount for the model, and Matano had to pay sticker price when he went to buy his own.

Matano continues to drive a Miata and attends rallies around the world, including gatherings in Belgium, Switzerland, Italy and Japan…and once drove along the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

A Philosophy of Automotive Design

Speaking with Matano about the Miata and cars in general is a unique experience. Each component of a vehicle’s design—from the door handles to the seat covers—is something he regards as much more than an inanimate object. In fact, during the design process, Matano sees himself as inhabiting the mechanisms, experiencing the driving experience from the car’s perspective.

“I’m inside the project,” he explains.

With Matano, car talk is elevated to a higher level. His eyes sparkle as he discusses the design life span of a vehicle and the subtle differences from one generation to the next. He speaks of owning a car so special that you want to greet it in the morning, treat it with kindness, and find new roads to introduce it to.

In the weeks leading up to the unveiling of the fourth-generation Miata in Monterey, Matano was visibly anxious. He desperately wanted a glimpse—a preview—but Mazda was holding out.

What if he didn’t approve of the modern version of his 1989 hit? How could he mask his reaction?

Fortunately, he had nothing to worry about. “The new car hit the target as fourth-generation Miata/MX-5. It is still recognizable as Miata/MX-5 from 100 yards away,” he says.

And so Matano did what a proud papa would: He hopped into the new model, smiled, and posed for photos.